James Rivington Tennis Dealer / Spy

First Published December, 2015

James Rivington, the son of a London book seller, was a true entrepreneur and, as you will read, a man of many talents. Seeking his fortune, he sailed to Philadelphia in 1760 at the age of 36 where he opened a book and stationery shop “Rivington and Brown” with a local partner. Less than one year later, leaving Brown in charge, he moved on to New York City where he started a printing business, which was situated at the foot of present day Wall Street.

His printing business flourished and he began to add other businesses under the same roof. He once again offered books and stationery and built a clientele among the city’s educated elite. In 1763, he opened a third book store on King Street in Boston while keeping his residence in New York.

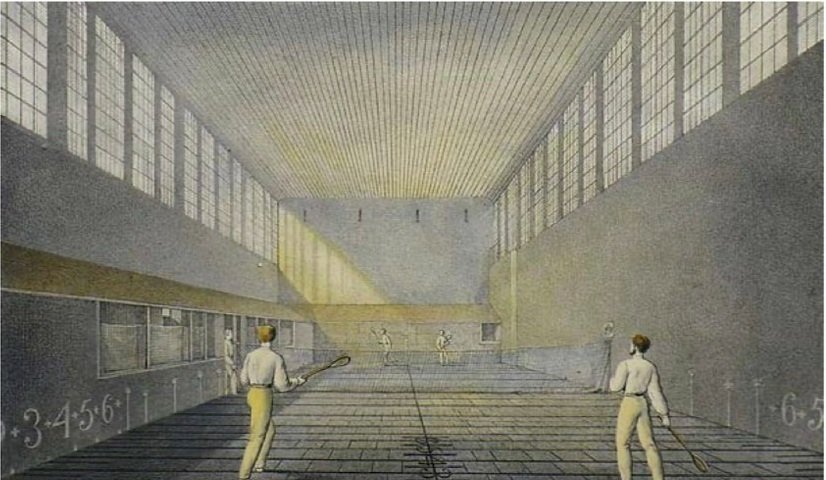

Fives Game

In one room of his book stores Rivington also sold imported English goods and in 1761 he advertised for sale in the New York Gazette “Croquet, tennis, fives, cricket, bowls, backgammon and dice” games. His sporting goods side business continued until at least 1766 when in a New York ad Rivington offered “battledores and shuttlecocks, cricket balls and best racquets for tennis”. The book stores in Philadelphia and Boston also offered sporting goods at this time, as well as musical instruments and artwork.

“Tennis” in 1761 meant the game “real tennis”, which Americans now call “court tennis”. In fact, the name court tennis didn’t evolve until after 1874 when an interloper named Walter Wingfield appropriated the name of “lawn tennis” for his new game when his alternate name “Sphairistike” failed to catch on.

Court tennis has a long history that dates back almost 600 years and was well established in the American colonies in the 1760’s. An April 4, 1763, ad in the New York Gazette advertised an auction of a house that “has a very fine Tennis-Court or Fives-Alley.” Fives was essentially a handball game that developed in Ireland as far back as the mid 1500’s. There is also evidence that ancient Egyptians and even the Aztec Indians of Mesoamerica played similar games.

Rivington’s businesses continued to prosper and in 1773 he began publishing “Rivington’s New York Gazetteer,” as well as continuing to print books and flyers. 1773 was also the year of the Boston Tea Party and soon American colonists were compelled to choose sides on independence from England. Approximately 80% chose independence and were labeled “Patriots”, while the remainder, deemed “Loyalists”, advocated remaining an English colony. His newspaper, at first neutral, began to move towards the Loyalist side by publishing articles critical of the Patriots and supporting King George III. His printed attacks eventually angered the Sons of Liberty enough that in 1775 they burned his printing business to the ground after destroying his presses and carting off his lead type to be melted into musket balls.

Rivington fled back to England with his family, but returned alone to New York in 1777 with new printing equipment and began publishing the “Royal Gazette” under the sponsorship of King George. Needless to say, The Royal Gazette regularly attacked the Patriot’s side in articles and editorials. Ever the businessman, he also opened a coffeehouse where he mingled with British officers.

Colonial Court Tennis

In September 1781, the French fleet met the British fleet in Chesapeake Bay in the “Battle of the Virginia Capes”, which led to the British surrender at Yorktown a month later when they were no longer able to evacuate or resupply their troops by sea, due to their naval losses. Effectively, this was the end of combat in the Revolutionary War, although the Treaty of Paris to end the war was not signed until 1783.

The tipping point of the Chesapeake Bay engagement it seems was that the French Navy had been in possession of the book of secret British signal codes, which had been printed and bound by the shop of one James Rivington. As a result, the French knew every move the English were to make as soon as the orders of Admiral Sir Thomas Graves were signaled to his fleet.

As it turned out, Rivington had been one of the six members of the famous “Culper Spy Ring”, which provided intelligence directly to George Washington on military activities in New York during the British occupation. He sent his information by binding it in book covers, which were then picked up and smuggled out of New York.

When Washington’s troops entered New York City in 1783 one of his first acts, to the surprise of everyone, was to visit James Rivington with his entire staff and a curious crowd in tow. While everyone waited outside, Washington had a private friendly meeting with Rivington and was heard discussing a book order with him as they emerged from their meeting. The point was made – James Rivington was a friend of Washington and would not be the subject of Patriot retribution, as many Loyalists were.

He was, however, shunned by most New Yorkers and spent the remainder of this life making a meager living selling books, even spending some time in debtors’ prison before his death in 1802.

So, does the ad from 1761 make James Rivington the first tennis dealer in the United States? I would guess “No”.

About one hundred years earlier on September 30, 1659, Peter Stuyvesant, the Dutch governor of New Amsterdam (now New York) issued a proclamation declaring October 15, 1659 a day of “Universal fasting and prayer” and goes on to preclude specific activities including “tennis and ball-playing” documenting the date of the existence of court tennis in the United States to at least 215 years before lawn tennis emigrated from England to our shores in 1874.

Good Collecting.